Filamentation: Difference between revisions

CSV import |

CSV import |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Filamentation == | |||

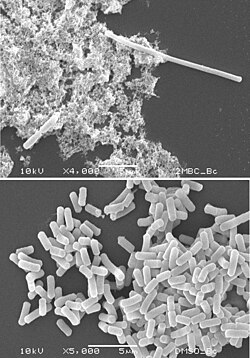

[[File:Filamentation_2.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Filamentation in bacteria.]] | |||

'''Filamentation''' is a process by which certain [[bacteria]] and [[fungi]] grow in a thread-like, filamentous form. This phenomenon is often observed in response to environmental stressors and can be a survival mechanism for the organism. | |||

== | == Mechanism of Filamentation == | ||

Filamentation occurs when cells elongate without dividing, resulting in long, filamentous chains of cells. In bacteria, this process can be triggered by various factors such as nutrient deprivation, exposure to antibiotics, or changes in temperature. The [[cell cycle]] is altered, leading to the inhibition of [[cytokinesis]] while [[DNA replication]] and [[cell growth]] continue. | |||

In [[fungi]], filamentation is a normal part of the life cycle, particularly in species like [[Candida albicans]], where it is associated with pathogenicity. The transition from yeast to filamentous form is regulated by environmental cues and involves complex signaling pathways. | |||

== Biological Significance == | |||

Filamentation can confer several advantages to microorganisms: | |||

* '''Survival:''' By forming filaments, bacteria can evade [[phagocytosis]] by [[immune cells]], as the elongated shape is more difficult for immune cells to engulf. | |||

* '''Colonization:''' Filamentous forms can penetrate host tissues more effectively, aiding in colonization and infection. | |||

* '''Biofilm Formation:''' Filamentation is often associated with the formation of [[biofilms]], which are protective communities of microorganisms that adhere to surfaces and are resistant to [[antibiotics]]. | |||

== Filamentation in Pathogenicity == | |||

In pathogenic bacteria, such as [[Escherichia coli]] and [[Salmonella]], filamentation can be induced by exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of antibiotics. This can lead to increased virulence and resistance to treatment. In fungi like Candida albicans, filamentation is crucial for tissue invasion and is a key factor in the organism's ability to cause disease. | |||

== Laboratory Observation == | |||

Filamentation can be observed in laboratory settings using various microscopy techniques. Staining methods can highlight the elongated cells, and time-lapse microscopy can be used to study the dynamics of filamentation in real-time. | |||

== Related Pages == | |||

* [[Bacterial morphology]] | |||

* [[Fungal life cycle]] | |||

* [[Biofilm]] | |||

* [[Antibiotic resistance]] | |||

[[Category:Microbiology]] | |||

[[Category:Cell biology]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:02, 15 February 2025

Filamentation[edit]

Filamentation is a process by which certain bacteria and fungi grow in a thread-like, filamentous form. This phenomenon is often observed in response to environmental stressors and can be a survival mechanism for the organism.

Mechanism of Filamentation[edit]

Filamentation occurs when cells elongate without dividing, resulting in long, filamentous chains of cells. In bacteria, this process can be triggered by various factors such as nutrient deprivation, exposure to antibiotics, or changes in temperature. The cell cycle is altered, leading to the inhibition of cytokinesis while DNA replication and cell growth continue.

In fungi, filamentation is a normal part of the life cycle, particularly in species like Candida albicans, where it is associated with pathogenicity. The transition from yeast to filamentous form is regulated by environmental cues and involves complex signaling pathways.

Biological Significance[edit]

Filamentation can confer several advantages to microorganisms:

- Survival: By forming filaments, bacteria can evade phagocytosis by immune cells, as the elongated shape is more difficult for immune cells to engulf.

- Colonization: Filamentous forms can penetrate host tissues more effectively, aiding in colonization and infection.

- Biofilm Formation: Filamentation is often associated with the formation of biofilms, which are protective communities of microorganisms that adhere to surfaces and are resistant to antibiotics.

Filamentation in Pathogenicity[edit]

In pathogenic bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella, filamentation can be induced by exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of antibiotics. This can lead to increased virulence and resistance to treatment. In fungi like Candida albicans, filamentation is crucial for tissue invasion and is a key factor in the organism's ability to cause disease.

Laboratory Observation[edit]

Filamentation can be observed in laboratory settings using various microscopy techniques. Staining methods can highlight the elongated cells, and time-lapse microscopy can be used to study the dynamics of filamentation in real-time.